Learning When Leaving

"Boy, do I have a lot to learn!" - Worst startup pitch, ever, right?

Yet, that probably the closest thing to truth you could say in a pitch--and I'd argue that the kind of people you should be backing are the people who can admit this and who never stop learning.

We don't do that a lot in the startup world. We reinforce the opposite--often out of necessity.

We've all seen this happen...

👉 Founders leave the company before the exit, or move out of the CEO role.

👉 Investors move from one firm to another or start companies.

👉 Employees jump from one startup to another.

In every one of those cases, the public narrative is generally a positive one and, too often, it comes with a dismissal of the missed opportunity or benefit of staying.

👉 Founders say they just like starting new things and the company got "too big to be fun".

👉 Investors move to "focus" or "go back to early-stage roots" or whatever.

👉 Employees throw their prior companies under the bus--often privately.

And sure, there's truth to many of these issues--but we never hear much about how leaving signaled a missed opportunity or chance to learn.

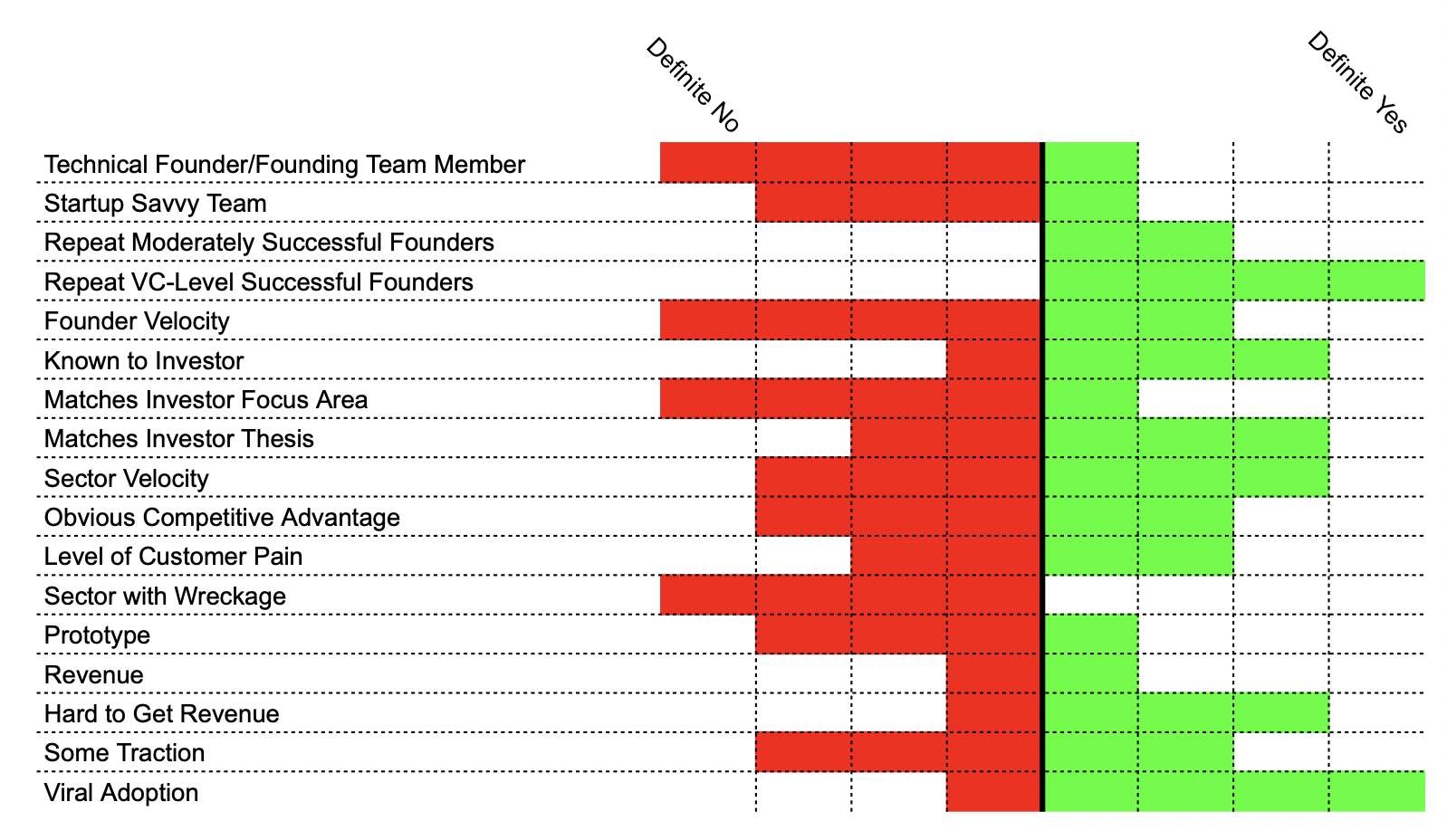

In my work as a coach to VCs, I've been reflecting on starting Brooklyn Bridge Ventures in 2012 given that starting their own fund is a goal of many of my coaching clients. It is seen as the pinnacle of career development as an investor--but what do we miss out on when we stick around to work with people who are more experienced at the expense of our own visibility and independence?

The due diligence question I got asked most when I started was whether or not I could continue to source good deals outside of First Round Capital, where I had worked as a Principal before starting my fund. I spent a lot of time telling investors how much I didn't need that brand because it was helpful to my fundraising pitch. I wasn’t being negative—I was trumpeting my ability to be independent.

I certainly wasn't going to say, "Oh, yeah, that's going to be hard--First Round is a great brand and has a tremendous network of resources that would make me a better investor. I'm going to need to work twice as hard to piece that together independently."

How successful would that fundraising have gone?

I have no idea, because that’s not what I did.

If I had that mindset, I would certainly have become a better investor and I can see that now. I don’t think I spent as much time as I could continuing to learn from mentors as I needed to.

Similarly, there are founders that I know who didn’t make it to the exit of their companies—asked to leave by a co-founder, replaced by the board, etc., or even those who left on their own who would be better founders the next time around if they took to heart lessons from their failure—and, yes, I said failure.

Anytime you part ways in any kind of relationship, unless the other person is begging you to stay, it’s a bit of a failure. Even if the parting is amicable, like starting something new after working for something else, at some level, they’re ok with letting you go.

We say things like, “They’re better off not being an employee/not having a boss” but we don’t acknowledge that, in some way, they failed as an employee.

Wouldn’t it have been better to master being a great employee and teammate before going off on your own? Wouldn’t that make you a better boss if you had been successful at the very thing you’re trying to teach the people working for you?

That doesn’t mean you’re a failure as a person or you didn’t create lots of value—but we’re far too dismissive about what we’re missing out on in these periods of transition. The same holds for personal relationships, too. Even if you realize you’re not a great match for someone, it’s worth taking stock of how you could have been a better partner.

A move to something better doesn’t mean you don’t still have lots to learn and improve over your last effort.