Raising a venture capital fund is hard enough. You’re going around to a bunch of people trying to convince them that you have what it takes to pick the big winners in a sea of aspirational companies that are destined for the scrap heap.

Now try doing that as a first time fund manager—without a long track record and lots of exits. Yet, that’s what has to happen if the profile of the check writers is going to be different than it is today. Barely 10% of the investing partners at VC firms are women and the number of investors of color is microscopic.

Since fundraising is often about who you know, and most people tend to be in networks that look like them, this exacerbates the problem of diversity in who winds up getting venture dollars.

One way to change this landscape, instead of waiting for VC jobs to open up is to go out on your own and start a fund to invest in the opportunities you see in your own community. Unfortunately, the way the Limited Partner landscape is setup and the nature of SEC rules, emerging managers are fundraising with their hands tied behind their back.

Most bigger institutions won’t invest in first time funds—and even those that do tend to need to write a minimum size check to make it worthwhile. They also don’t want to be more than 20% of a fund. The reality of fundraising for a new, smaller fund is that you’re mostly going to wealthy individuals to raise.

Here’s where it gets tricky.

You have to be an Accredited Investor to put your money into a VC fund, but the way the system works, there are many accredited investors who wouldn’t be able to meet the minimum investor requirements the system forces VCs into.

The rule on a fund is that unless everyone is a Qualified Purchaser, meaning they all have $5mm in assets, you’re stuck with two different types of limits on how many investors you can have. If your fund is no more than $10 million, then you can have up to 250 (or, 249), but if you get above that, it’s 99.

So, if you want to have a certain sized fund and you’re capped on the number of LPs, simple division gets you at a minimum number each person has to invest to hit your goal.

This is the 99 Investor Limit Problem that Brad Feld describes here.

I guess the idea has always been that for something so risky as VC, you only want “sophisticated investors” involved—with “already rich” being a proxy for sophisticated. God forbid the average person gets a cut of the pre-IPO growth of all of these companies that hit the public market like a falling knife.

The rich people got to invest in Uber for a 5,000x return, but the rest of the public had to wait to get a…

* checks current share price *

…negative twenty-five percent return after it went public.

Point being, you’re off pitching to rich people—and not just rich people—super rich people way over and above the minimum accredited investor numbers.

Well, what do we know about rich people. First off, they tend to be overwhelmingly white and male. We have heard about pay gaps in this country—about the cents on the dollar various groups are making compared to white men, but the wealth gaps are even worse. For every $100 of wealth in a white family, the average black family holds a little more than $5 worth of wealth—and wealth is a better predictor of who can invest in venture capital, a long term asset class in which people are only putting part of their money into because if its high risk.

This is all context around what the investor number caps mean for the kind of money you need to ask people for in order to build a decent venture capital fund.

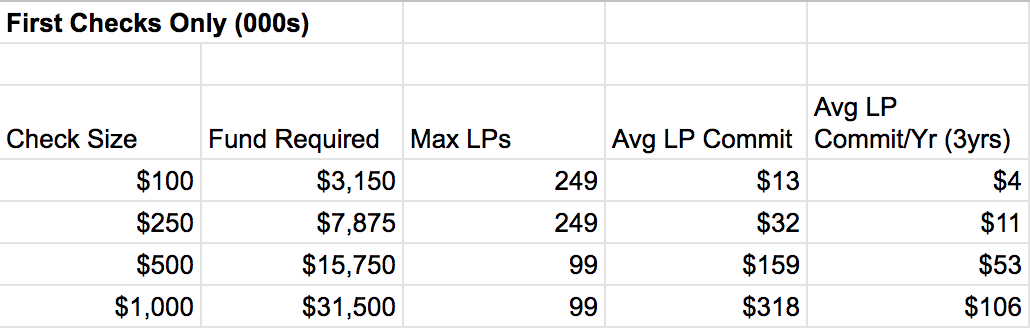

Let’s say you want to go raise a small seed fund. You’re not even looking to go big. You want to write $100k checks and be done with it. You can’t really lead rounds and you can’t support them over time. Here’s what it looks like in terms of people able to raise from just “normal” wealthy people, assuming they’re not all super-wealthy (Qualified Purchasers).

Ok, so assuming with some recycling, maybe you get to 95% invested across 30 deals, if you maxed out on the number of LPs allowed, each person would only have to do about $4k per year for three years. That’s not too bad and I think someone who is well networked actually has a shot at this.

But, look at how the numbers change as you want to write more meaningful checks.

If you want to lead seed rounds—backing founders from diverse and underrepresented communities, for example—you’re going to need bigger checks, especially if capital willing to co-invest in these communities is sparse.

Look at what happens when you cross over into that $500k initial check size—your fund busts through the $10mm limit for an “angel fund” and now your base of allowable investors shrinks to 99. That means that the minimum investor who fulfills their three year investment period commitment goes from writing a $4k check a year to over $53k, even though the fund is barely 5x the size.

Investing over fifty grand per year in a VC fund is some serious dough. When you separate the universe of potential VCs between those who can source 99 $50k check writers per year and everyone else, the stats on who is connected to wealth within their network is going to dictate that group is a less diverse pool.

Now, look at the numbers if you want to have a more substantive strategy that continues to support these companies over time with follow-on capital.

At 50% reserved, you literally cannot create a VC fund that is in a position to lead using these limits unless you know people who can write checks of $80k per year. Even writing checks of $250k is going to be a struggle, because going from $100k to $250k means you need about 7x the average annual LP check.

Now imagine if the limit was 500 investors. Thanks to fund administration platforms like Carta, the technology is there to easily manage these pools of investors, so that’s not a problem.

You would have this huge network of potential fund supporters and here’s what the stats would look like:

This makes a huge difference. Now, you could be out writing half million dollar checks and reserving half your fund for follow-ons, and each underlying investor is only responsible to fund $16,000 per year. Sure, not everyone has that, but way more people can do that than $80k.

Plus, at this level, you could get those same investors backing multiple funds at a time, which is better for competition among funds, and also broadens the base of who gets experience in VC. They’d also be more likely to keep backing these funds for their Fund II, III, etc., and not stop putting money to work while waiting for those early payouts from the first fund.

It’s also better for the limited partner. No longer do they have to risk huge chunks of capital to get exposure to this risky asset class. More LPs could get involved with less money each—and those investors will also tend to be more diverse.

The vast majority of LPs I’ve had to turn down because they couldn’t meet my minimum check size of $250k were women and people of color. I’ve even stretched to be inclusive of those groups and lowered the minimum for some, and it’s still incredibly difficult. For every “stretch” LP I take below the minimum, I have to find a bigger one to balance them out in the average.

People worry about over-investment in the asset class, but what we’re talking about here is the tiniest part of the asset class. You could create 40 funds of $25 million each and it wouldn’t equate to a quarter of the new money that WeWork got after its disastrous implosion.

What you would get is a whole bunch of new startups blooming, able to hire because they have funding and more chances for larger VCs down the road to have backable companies to take to the next level. Plus, you’d probably get a lot of diversity in the types of companies being backed, the approaches of the founders and the geographies of where they are starting.

Lowering the bar on how much an LP has to lockup in a fund makes raising capital for new and emerging managers easier, provides more accredited investors access to the asset class, and undoubtedly would diversify the pool of people running funds.