You hear this from VC’s a lot: “We need to own X% of your company to make our returns.”

They back it up with sensible math—owning 20% of a billion dollar outcome returns a $200mm VC fund, and, of course, you’re trying to at least return the fund. So, no one really questions the ownership model.

Yet, when you buy shares of Apple or Facebook, you don’t even think about what percent of the company you own. How then, do you expect to make money when you’re buying on the public market?

Everyone knows the answer to that.

“Buy low, sell high.”

Seems like that should translate over to the venture world, too. After all, all we’re really doing as VCs is buying shares, aren’t we? How come VCs don’t think about it that way?

There are two reasons. First, price discipline doesn’t work in overly competitive markets. When there are too many funds in a market segment trying to do the same deals, keeping your entry price reasonable is going to get you shut out of a lot of deals. If you’re a first check lead VC for pre-seed rounds in New York, you can keep your head on when it comes to price, because you’re not going against that many other people.

If you’re in SF trying to fund AI companies from YC, good luck with your price discipline.

Second, you can only get so many dollars into “cheap” seed shares. If you raise $100mm, you can’t put it all to work upfront because the rounds aren’t big enough—so you have to deploy more capital later (and more expensively). Dilution becomes the enemy. You tell your investors that you don’t want to own a smaller and smaller percent of your “best” companies. You need to write bigger checks to maintain ownership.

What you’re not saying to your investors is that you’re buying more and more expensive shares at a lower return.

I guess that doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Of course, there are other non-financial reasons to follow-on. Brooklyn Bridge Ventures, my fund, does small follow-ons (10-20% of the original investment) that enable the founder to say that everyone is continuing to participate. That means you might get $400k upfront from me in your seed or pre-seed round when the money is hardest to get, plus a term sheet that helps wrangle everyone else, with a follow on of $50k in whatever comes next. The vast majority of founders are completely willing to get more money upfront when they haven’t proven much yet in exchange for less money later when there is enough risk off the table to get others to participate instead.

Also, funds that lead Series A, B, and C rounds have serious capital needs that extend over the life of a company. They’re not only leading larger rounds, but may need to bridge companies they’ve otherwise made large investments into that have higher burn rates. Sometimes, you’re the only one around the table who wants to do a Series B and that requires real cash.

That’s not what seed funds are doing. They don’t have enough cash to bridge a Series C round anyway.

Seed funds specialize in doing a lot of work for not a lot of money—and I suspect that’s why they’re getting larger. We do the work of sorting through the pitch decks of everyone and their mother, finding the diamonds in the rough, helping them turn an idea into something that looks like a company—and we do it for a fraction of the management fees of our later stage counterparts.

The incentive to want a larger fund is real—more staff, better office, better salaries—but the investment strategy of holding back your capital to pay up for pricier shares really doesn’t make much sense from a returns perspective if you ask me.

I took the time to model out some returns using share price as a basis—to figure out if the price you’re paying when you buy up is worth the difference in the outcomes.

Here’s a very plain vanilla model. It doesn’t take into consideration fees, carry, options, down rounds, or recaps. It’s just a model of the share price of a company going up and to the right smoothly until it exits for $300mm, and the outcomes for the shares purchased in each round of financing.

Seed round investors get a tidy 18.2x return—which means in this model I’d return half my $15mm fund on one $300mm exit—since I front load most of my investment into the first round and write checks of $350-400k.

Later round investors who pay up get less, obviously.

Keeping fund size the same, they also wind up putting less into the first round of their winners while at the same time putting less into the losers. They hold their cash back until they have more data, and lean in as a company is outperforming.

That creates a tradeoff of paying up for more information.

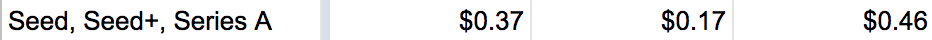

How much do they hold back? This is the data of what your investment dollar distribution looks like if you’re doing the pro-rata of each of these rounds.

Obviously, if you’re only doing the seed, you’re putting 100% of the fund into the seed. If you’re holding back to do your pro-rata in a seed+ round, you’re holding back about 32 cents on the dollar and putting 68 cents in upfront. Doing your pro-rata in the Series A? That means you’re only going to get 37 cents into the cheapest round and you’re holding back the other 63 cents for later, more expensive investing. That means your winners are giving you just under a 9x return, because, on average you’re paying twice as much.

At least you’re avoiding putting more of these dollars into the losers, through, right?

Yes, but you have to be really good at that to make it a better fund overall—like, REALLY good.

How good?

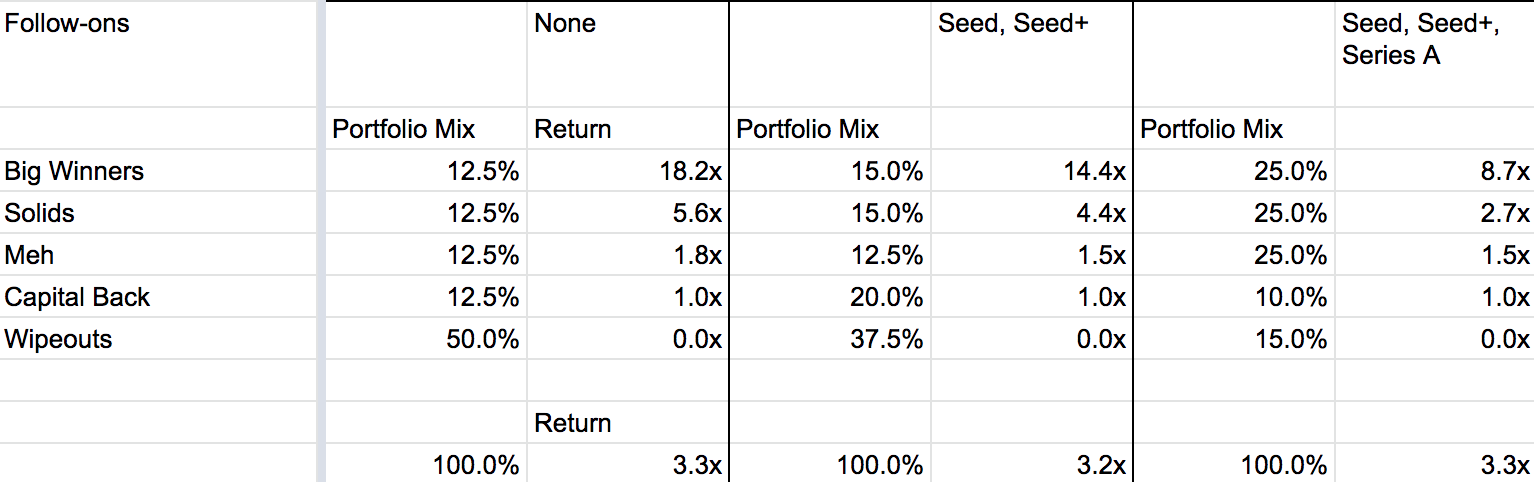

I created a few fund mix scenarios and estimated what the overall fund return would be given that mix.

Here are the following outcomes:

Big Winners: Exit at $300mm No downrounds

Solids: Exit at Series B Post No downrounds

Meh: Exit at Seed+ Post No downrounds

Capital Back: Capital Return

Wipeouts: No Return

I don’t like modeling things with billion dollar outcomes because they’re rare and you shouldn’t base your investing on getting one.

Then, I estimated a seed fund’s mix of dollars necessary to get a 3.3x return without follow-ons:

It’s not unlike what you hear a lot—that about 10% of the fund or so generates most of the returns. Throw in a couple more solid returners, a few singles and doubles, and you’ve paid for the fact that half your portfolio was a complete wipeout.

Some call it lucky. I call it disciplined—because you’re buying in cheap enough to make your winners return enough to make up for the duds.

If you keep on going through the seed+, you’ve got to be a bit better allocating your dollars. Only about a third of your dollars can go into the duds and you’re up closer to 15% of your dollars going into winners to get the same fund return.

The pattern continues through the A. If you’re following on that far, you’ve got to be that much better in your dollar allocation to get the same returns:

How much better? Well, now a quarter of your portfolio has to be invested into the big winners and only 15% can be in the duds. That’s actually kind of a problem—because, at seed, a lot of funds will admit that half your seed bets aren’t going to make it—but our math earlier gave us the following:

This is the dollar distribution of your investments when you do pro-rata through the A. About 37% of your dollars will be in the seed rounds, and if half of them went bust, then you definitely invested more than 15% of your fund in those rounds. Not sure how you get around that math—unless somehow you’re able to know ahead of time they’ll be duds and you put less in them. It begs the question of why you invested in the first place.

Obviously, the math and estimates here are super variable, but the point of this is that we have walk right up to the edge of suspending reality to just get the same returns as in the no follow-on model. Imagine what the math needs to look like for this model to be demonstrably better by following on all the way through.

Keep buying up, and the pattern continues…

Follow on all the way through a Series C and you’ve got to put in a full 90% of your dollars into your big winners to get in the ballpark of the no-follow model. Again, that’s going to be super hard to do, because if you invested through the A on all your companies, you put in about 15% of your dollars into the duds…

Here’s how your dollar into a company shakes out if you’re doing pro-rata across rounds. In a one company model, it’s about 30%—but since half your seeds don’t make it to A, you cut the 14% A round follow in half. I don’t know how many seeds make it to seed+ or how many seed+’s there are, but the point is, you don’t have much margin for error if only 10% of your portfolio is allowed to be invested in the duds.

Following on is just really, really hard work if you’re going to get the same returns—and you can’t afford to follow on big into a company into the Series B, C, and beyond and not get a big outcome. That will sink a fund in a hurry.

The nice thing is that you don’t need the same returns, because you have more management fees and a bigger fund—so less carry on a larger base is still more money.

If you’re a larger LP, you don’t have much choice to put the money to work either. If you need to invest $25mm at a time, you’re still better off in venture capital than in the public market if you can access good managers. If you’re a smaller investor, however, and you can get your check size into any fund—the math points to trying to get into the fund buying in at the lowest average share price across its portfolio. It’s a lot easier to make a better multiple of return there—and if it’s all the same to you check-size-wise, then smaller seems better.

I’m sure someone else can build a much better model than I can, and throw in a lot more complexity around return expectations—but to even build a model at all probably makes me top quartile in terms of GP analytics. I’m absolutely stunned at how few managers, especially new ones, ever bother taking a shot at doing any fund cashflow models. Too many times I hear echos of what’s been talked and blogged about without any data behind the thinking. What might work for a larger fund may not hold true for a smaller one—so before you take someone else’s strategy as your own, take the time to do some math around it.

Also, we all need to play to our strengths. Some investors are better at dealing with more data—and others might be better “first pitch” hitters. What’s important is that you’ve thought through how good you need to be if the data says you need to be better than average to make your math work.