Are we in a bubble?

And if so, when will it burst?

Everyone likes to debate it, and statistically, almost no one gets it right. Not only is it notoriously difficult to time the market, but even if you did, you'd miss out on individual winners. Sam Altman of YC recently pointed out that pulling back during the downturn in 2008 would result in several big misses:

In October of 2008, Sequoia Capital—arguably the best-ever in the business—gave the famous “RIP Good Times” presentation (I was there). A few months later, we funded Airbnb. A few months after that, a company called UberCab got started.

Those companies would have not only returned any fund that invested in them, but would likely return an entire career's worth of investing over the course of several funds.

Still, no one wants to be the one holding the back when things do pop--and they will, right? Doesn't every good run have to come to an end? Will this bubble also end in a blaze of glory with companies shutting down left and right in a massive startup apocalypse?

Probably not, since that's not exactly what happened the first time around.

Would you be surprised to know that almost half of the dot com companies founded when the boom started in 1996 were still around in 2004--four years after the peak of the NASDAQ?

A paper by two University of Maryland researchers who arrived at that number concluded the following:

"...Observed financial losses did not, in fact, equate with firm failure...tectonic changes in the

underlying entrepreneurial landscape were obscured by the financial bust. Against a

highly salient backdrop of destroyed market value, we interpret the high survival rate of

Dot Com firms to mean that many of the business ideas that flowered during the Dot

Com era were basically sound. In other words, good ideas were oversold as big ideas.

Most internet opportunities were of modest scale – often worth pursuing – but not usually

worth taking public. Because most internet business concepts were not capable of

productively employing tens of millions of dollars of venture capital does not mean they

were bad ideas."

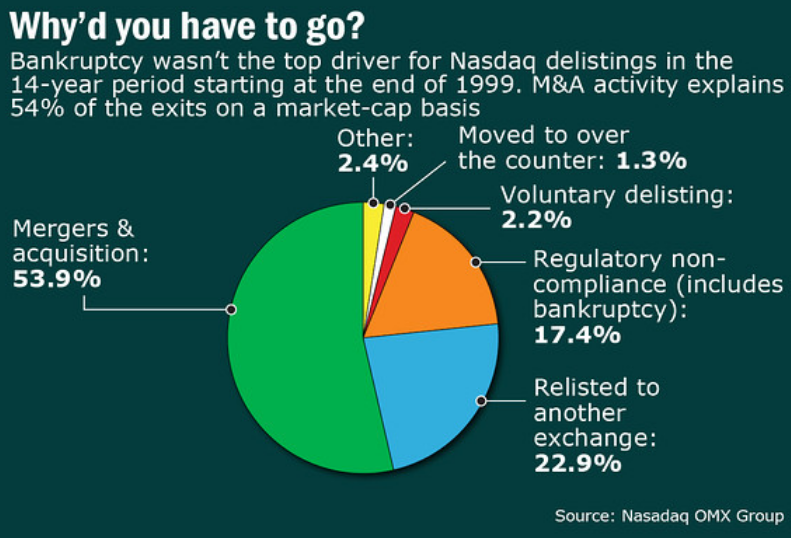

Another way to look at it is to track how companies wound up leaving the NASDAQ Composite.

These companies were, even in the worst times, worth sometime to someone.

So if you think what's going on today is a repeat of what happened 15 years ago, you may be right--but I think what you'd be right about is that "good ideas were oversold as big ideas".

There are lots of those around. I have a feeling that a lot of these "on demand" companies aren't going to be as gamechanging as we think--and will come back down to earth with valuations that look more like temp agencies than the next big thing.

So where does that leave us?

I have no doubt that companies like Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, Slack, Snapchat, Pinterest, Stripe, Square, etc are real businesses. They're not going out of business, nor are 100's of other new companies created during this time. They'll be around 10 years from now.

But at what valuation? That is the real question.

It took the NASDAQ fifteen years to get back to it's March 2000 peak--and I think that it's possible we're looking ahead at the same kind of period, but one without the huge trough. Why? Because companies today have way more revenues than the companies that went public or had huge up rounds back then. And, they aren't necessarily revenues from other dot coms. They're consumer, SMB and enterprise revenues--maybe not enough to justify their valuation, but much much further from zero than companies in the past. They're real businesses that would have had great outcomes if not for the go go growth round unicorn creation machine we've got going.

My own personal prediction is a long period of market stagnation at the top end. At some point, the music stops, the greater fool theory fails to find a greater fool, and companies start a mad dash to break even.

Enter the Zombie Startup Apocalypse.

What happens if you can't grow enough to sustain your multi-billion dollar valuation and there aren't any more growth funds or hedge funds willing to give you another up round? That's when the heads start rolling.

Any one of these unicorns could be profitable right now. All they would have to do is cut a few hundred people or two, and stop buying growth with venture dollars. That would actually be pretty good for the talent market--it would bring salaries back down to normal.

Instead of paid acquisition fueling an up and to the right hockey stick, these companies would grow organically. Retention, referral and growth hacking experts would be in high demand, asked to squeeze blood from a stone in order to grow a userbase without paid acquisition. All of the sudden, Facebook ad pricing would become reasonable enough again for startups to start using it.

With growth rates reduced, IPOs would be even tougher to come by--but companies would survive. They might even find themselves operating more efficiently than they ever had been--newly focused on core metrics.

Each month, they'd tick up just a little bit. Tick. Tick. Tick.

Eventually, they might be worth what they're valued at now to the public market or to an acquirer, but not for a very long time. Meanwhile, they'd just continue to go somewhat sideways and maybe a little bit up.

Founding teams, bored of a decade of being tied to one company, would start to churn out.

Seed and early investors might get bought out--perhaps by the growth funds that were fueling the valuation growth. Why invest at top dollar in the last round, when you can offer liquidity to early investors at a huge discount to the last round? It would still make for a huge return to the early investors. The later stage guys would just have to wait longer for the company to grow into its valuation.

If you're a long term investor, you'll realize that the market for new technology continues to grow. Innovation continues to disrupt older industries, create opportunities, and create new streams of revenue. These sound fundamentals drive the venture capital market over the long term.

In the short term, the sector is susceptible to a lot of hype and valuation volatility. Financial fortunes around hype cycles are made and lost, but the underlying idea that new technologies are worth investing in at reasonable valuations remains sound.